Customer-targeted phishing is when criminals impersonate your brand to trick your customers. They pose as your support team, your billing department, or your security alerts. The goal is simple. Steal credentials, one-time passcodes, personal data, or money. The bait can start via email, SMS, ads, search results, social DMs, and sometimes voice (vishing) or callback scams, but it usually ends on attacker-controlled external infrastructure, such as lookalike domains and cloned pages.

A takedown is the process of removing or disabling the attacker's infrastructure, meaning having a fake site pulled down, suspending an impersonating social account, requesting the suspension or removal of a malicious ad, or getting a fraudulent domain blocked or taken offline by the hosting provider. The point is to disrupt the customer harm pathway as quickly as possible, then remove the pieces that enable the scam to keep running.

A workflow is how you make takedowns repeatable under pressure. It’s the agreed sequence of steps, owners, evidence requirements, escalation paths, and timelines that turns “we got a report” into “distribution stopped, and infrastructure is gone.” Without a workflow, teams improvise, leading to delays, handoffs, and duplicate work while attackers keep converting customers in the background.

What does “customer-targeted phishing” actually look like?

Common attacker channels

It looks less like a single phishy email and more like a customer journey that was designed by someone who really understands your brand. The attacker steals your logos, your tone, your product names, and even your support language. Then they drop the trap where customers already are. Inbox, SMS, paid search, marketplace listings, social DMs, QR codes, and phone calls. The most effective campaigns do not ask for something obviously shady. They ask for something that sounds normal, like “confirm your account,” “reverse a charge,” “verify a suspicious login,” or “reconnect your service.”

Why these phishing campaigns convert

The scam almost always has multiple moving parts. A short link or ad lands the customer on a lookalike domain with a cloned login page. If credentials are entered, the flow might immediately pivot to a one-time password (OTP) grab, a fake “secure chat,” or a phone call to “support,” where the customer is coached step-by-step. Sometimes the goal is account takeover. Sometimes it is a direct payment. Sometimes it is harvesting enough personal data to reuse later. Either way, the infrastructure is built to convert, not just to deliver a message.

Signals customers don’t expect in legitimate journeys

A useful way to spot it at a high level is to look for friction points that real customer journeys don’t have. Sudden urgency, unusually specific instructions, off-brand URLs, “security verification” steps that push customers off your known channels, and support touchpoints that don’t match your real processes. When you see those patterns, you’re not dealing with one bad URL. You are dealing with a campaign that can rotate domains, pages, and channels quickly while keeping the same victim flow. That’s why your response has to focus on the whole chain, not just the first reported artifact.

Why the victim journey matters more than the initial lure

The attacker’s goal is to walk a customer through a flow that ends in payment, credential capture, one-time password (OTP) theft, or account takeover. They’re designing a conversion funnel. Each step is meant to reduce suspicion and increase urgency, usually by mimicking real support and security processes your customers already recognize. By the time the customer reaches the final step, it feels like they’re fixing a problem rather than getting scammed. That’s why the infrastructure matters. The fake site, the spoofed number, and the scripted chat are the mechanisms that turn a lure into a real loss.

That flow can include multiple handoffs. A fake “security alert” email leads to a cloned login page. A successful login triggers a “call support to verify” step. A call leads to an OTP request. You end up with fraud losses and angry customers. Security gets a spreadsheet of URLs. Support gets 400 tickets. Marketing gets blamed for “brand trust issues.”

Customer-Targeted Phishing takedown vs Traditional phishing response

Employees live behind controls. Customers do not. More precisely, you manage corporate endpoints and corporate email security. You do not manage your customers’ devices, inbox rules, or browsing environments. Your response can’t rely on endpoint tools, internal email gateways, or policy training that assumes a managed device.

Why do takedowns fail even after the first report?

“Report and remove” is an action, not a workflow. Most teams can get a single URL taken down. The problem is that the URL was never the campaign. It was one disposable asset in a rotating set, and attackers expect it to burn.

What you’re really up against is a connected bundle of infrastructure. Lookalike domains, landing pages, redirect chains, ad destinations, impersonating social accounts, and sometimes spoofed phone numbers or chat widgets. If you remove only the first reported artifact, the campaign continues converting customers to the next domain or channel. That’s why takedowns fail. The response stops at the symptom instead of dismantling the system that makes the scam repeatable.

Attackers rebuild faster than ticket queues move

Domains churn. Hosting changes. Pages get re-skinned. Links get swapped. If you remove one page and call it a day, you’re swatting at one pop-up after another, with no idea when or where the next one will surface.

Worse, attackers often reuse infrastructure across multiple brands. If you’re only reacting to what your customers report, you’re seeing the campaign after it is already converting.

Ownership gaps slow everything down

Security often owns “phishing.” Brand teams often own “trademarks.” Fraud teams own “loss.” Support owns “angry humans.” Legal owns “language.” Nobody owns the end-to-end customer-targeted phishing takedown workflow.

That split sounds reasonable on an org chart, but it’s brutal during an active campaign. A customer reports a fake site. Support logs a ticket. Security wants validation and artifacts. Brand wants to protect reputation and messaging. Legal wants specific evidence and approved wording before escalation. Fraud wants to know whether it’s actually converting. Meanwhile, the attacker rotates domains and keeps scamming victims.

So the work happens in the cracks. It becomes a chain of handoffs, and every handoff adds hours. Hours turn into more victims, more chargebacks, more account recovery, more angry customers, and more internal “why did this take so long” conversations. Attackers love hours, because time is the one resource defenders hand them for free.

How do we run a customer-targeted phishing takedown workflow that actually works?

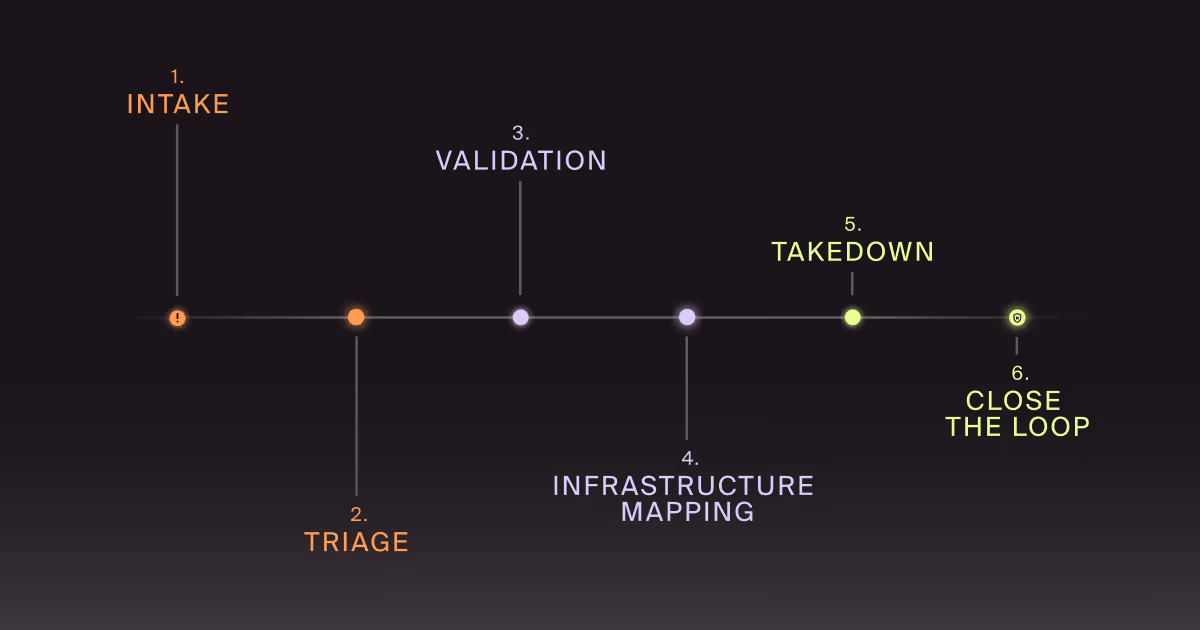

You run it like an operational pipeline, not a series of heroic one-offs. Intake. Triage. Validate. Map infrastructure. Execute takedown in parallel. Reduce re-entry. Close the loop.

The point of a takedown workflow is speed with consistency. Everyone knows what happens next, what “good evidence” looks like, who can push which levers, and what gets escalated versus handled on the spot, removing the slowest part of response, which isn’t technical work. It’s the internal back-and-forth when a report lands and the organization has to reinvent its own process.

Here’s the workflow we build with teams when the goal is outcomes. The following steps are designed to stop customer harm quickly, then dismantle the infrastructure that makes the scam repeatable.

Intake. How do we capture the right signals without drowning?

You need a single place where customer reports, SOC findings, fraud signals, and brand monitoring all land with consistent fields.

At minimum, capture: reported URL or account, channel (email, ad, social, SMS, call), brand element abused, customer impact reported, and time first seen. Then attach evidence, because you will need it for escalations and faster takedowns.

Capturing the right signals is where external scam website monitoring earns its keep. It fills the gap between “customers reported it” and “we found it early.”

Triage. What do we decide in the first 30 minutes?

Decide whether it is real. Decide how much harm it is doing. Decide what track it belongs on right now.

We like a simple scoring model that focuses on customer exposure and conversion risk. Is it actively distributing? Is it imitating a login or payment flow? Is it tied to a known scam pattern? Is it being boosted by ads? Does it mention urgent security language? If yes, it goes to rapid takedown. If you need a broader structure, anchor it in an impersonation attack response plan mindset. Pre-made decisions beat “let’s hop on a call” every time.

Validation. How do we confirm the scam without putting our team at risk?

Confirm the victim flow using safe methods. Use isolated browsing, instrumented captures, and controlled test accounts where appropriate. Record the redirects. Grab page artifacts. Capture contact points like phone numbers, chat widgets, payment rails, and form endpoints. Validation is “what does the attacker want the customer to do next?” That “next” is what you disrupt. Do not enter real customer credentials or interact with payment flows. If you must test form behavior, use non-production test accounts approved by security and legal.

Infrastructure mapping. What do we remove besides the obvious URL?

Map the campaign like an attacker would. Identify the domain, hosting, DNS, TLS, redirect chain, landing variants, and any connected assets such as social accounts or ad destinations.

Look for clusters. Shared page templates. Shared tracking IDs. Reused phone numbers. Reused payment destinations. Similar naming patterns across domains. You’re trying to remove the campaign’s legs, not just its shoes. This is where a Digital Risk Protection (DRP) program becomes operational instead of alert-driven.

This is where a Digital Risk Protection (DRP) program becomes operational instead of alert-driven. Mapping shared infrastructure, templates, and reuse patterns turns scattered external signals into coordinated takedown actions.

This is one reason we talk so much about digital risk protection. DRP is a way to operationalize external intelligence into actions.

Takedown. How do we execute fast without waiting on one lever?

Run parallel tracks. Domain. Hosting. Platform. Payments. Distribution.

If it’s a scam site, pursue scam website takedown actions with the most direct path first. Hosting and platform removals are often faster than DNS battles, but not always. Prioritize the lever that is most likely to reduce new victims fastest for this specific campaign. If paid ads are distributing it, cut distribution while infrastructure removal is in progress. If a spoofed support number is involved, pursue telecom and platform reporting while you work the site.

The key is sequencing for impact. Stop new victims first. Then remove the underlying assets. Then reduce re-entry.

Close the loop. What do we change after the takedown?

A takedown is a treatment. Close the loop with prevention changes that reduce the next wave.

Update customer-facing help content and in-product warnings where appropriate. Tune monitoring based on what you learned. Add detection patterns for lookalike domains and repeated templates. Hand off indicators to fraud teams for transaction monitoring. Feed support with crisp “what to tell customers” guidance that doesn't sound overly legal.

If the campaign used human manipulation in a repeatable way, connect the dots to social engineering defense and human risk management. Customer-targeted attacks often bleed into employee-targeted attacks, especially when helpdesk and finance are involved.

What should we measure to prove the workflow is working?

Measure speed and impact, not volume.

Start with time-to-triage and time-to-disruption. Then track time-to-removal for each takedown lever. Add repeat rate: same template, same phone number, same redirect chain, new domain. If the repeat rate stays high, you are removing symptoms.

Finally, measure customer harm proxies. Support ticket volume for the campaign. Fraud loss tied to the flow. Login abuse spikes. Password reset spikes. The numbers will never be perfect, but directionally, they tell you whether the workflow is reducing real-world damage.

How do we keep brand, legal, fraud, and support aligned without endless meetings?

Define roles once. Then automate the handoffs. Security owns validation and infrastructure mapping. Brand owns customer messaging and escalation paths with platforms. Legal provides pre-approved language and thresholds. Fraud owns loss tracking and customer recovery workflows. Support owns customer intake and provides consistent guidance.

Most importantly, agree on what doesn’t require a meeting. Pre-approval beats consensus theater.

How do we reduce the “re-entry” problem after a takedown?

Assume attackers will come back. Plan for it.

Build brand monitoring rules based on patterns. Watch for domain permutations, reused templates, and repeated contact methods. Keep a campaign library. When a new report arrives, match it to known clusters and fast-track it. This is where a DRP program has to be more than alerts. Doppel helps teams cluster related attacker infrastructure, validate victim flows safely, and generate evidence packages that speed platform and provider takedown requests, through an operational workflow so teams can move fast without improvising every time.

Key Takeaways

- Customer-targeted phishing is a multi-channel campaign problem, not a single bad URL problem.

- A working takedown workflow prioritizes disruption first, then removal, then re-entry prevention.

- Validation and infrastructure mapping are what turn “reporting” into repeatable outcomes.

- Measure time-to-disruption and repeat rate to prove you are reducing customer harm.

Customer-Targeted Phishing Takedowns That Stick

If customer-targeted phishing keeps resurfacing under new domains, that’s not bad luck. It’s a workflow gap. Attackers are treating your brand like a reusable template, and they’ll keep swapping infrastructure until the takedown effort becomes too slow to matter.

If you want to pressure-test your current customer-targeted phishing takedown process and identify where it’s slowing, we can walk through a real example and map out what “fast” looks like for your team. We’ll pinpoint the steps that create the delay. Evidence collection, internal handoffs, platform escalation, legal approvals, and repeat offenders that keep slipping back in. Then we’ll tighten the workflow with clear owners, parallel takedown tracks, and metrics that prove disruption is occurring.

If that sounds useful, reach out. We’ll help you move from “we removed a URL” to “we dismantled the campaign and reduced re-entry.”